Hundreds of public institutions across West Bengal and other parts of India have benefited as a result of Water For People’s work Shutterstock

According to data collected by The World Bank, India has 18 per cent of the world’s population but only four per cent of its water resources, making it one of the most water-stressed countries in the world. In summer time, water becomes as precious as gold in large parts of India, with climate change exacerbating an already hazardous situation.

Born out of the American Water Works Association (AWWA), Water For People (WFP) is an international non-profit organisation with its headquarters in Denver, Colorado. Its Indian wing, Water For People India, has been one of the most important actors in mitigating India’s water crisis for two-and-half decades.

Earlier in November, members from WFP’s global team and some supporters visited West Bengal to understand the impact of the work being done in the state. Collaborating with WFP on their visit was Flying Squirrel Holidays, which specialises in providing seamless, customised vacations around the world.

My Kolkata caught up with WFP India — country head Bishwadeep Ghose, West Bengal state-in-charge Sujata Tripathi and programme lead Dipa Biswas — and Niloy Nag, founder and managing partner of Flying Squirrel Holidays, to understand more about West Bengal’s water problems.

Edited excerpts from the conversation at WFP’s Kolkata office on Gariahat Road follow.

A sustainable ecosystem instead of one-time services

(L-R): Dipa Biswas, Bishwadeep Ghose and Sujata Tripathi from Water For People India alongside Flying Squirrel Holiday’s Niloy Nag Sourav Nandy

My Kolkata: How long has WFP been working in India and West Bengal? What brought you here?

Bishwadeep Ghose (hereafter Ghose): We’ve been working in India since 1996, when we began our operations in West Bengal with a programme on arsenic mitigation in the districts of North 24-Parganas and Nadia. That was the catalyst behind coming to Bengal. I suppose it was also helped by the fact that it’s easier to work in Bengal, since people are more politically and socially aware and are ready to be mobilised to partake in different activities.

Over time, we expanded our initiatives in India to create sustainable access to quality services for water and sanitation facilities as well as hygiene awareness, especially for vulnerable and underserved communities.

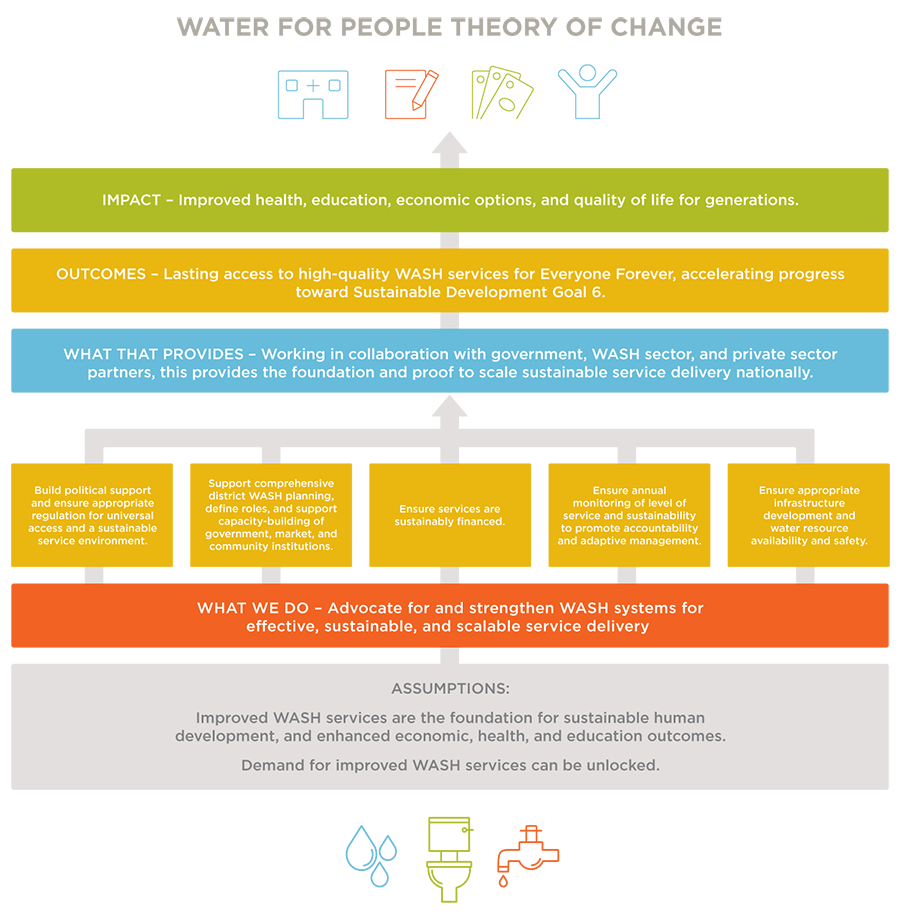

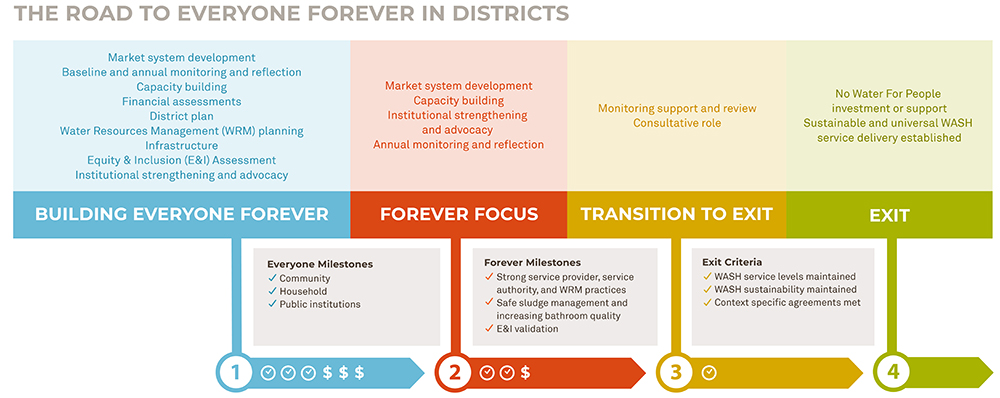

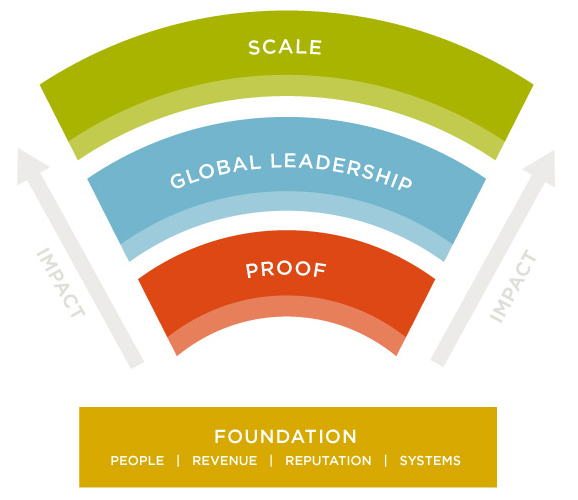

We have an impact model called Everyone Forever, which translates into universal and sustainable access to services. It relies on building a sustainable ecosystem involving service providers and service authorities, instead of one-time services, so that people can benefit from our work in the long-term.

Currently, our work in India spans 28 districts across West Bengal, Bihar, Odisha, Assam and Maharashtra. We have a team of around 100 people working in India, including those in our field offices in Birbhum and South 24-Parganas. We’ve reached more than 1.2 million people through our different projects. Be it in Bengal or in the rest of India, we work closely with the government, public and private institutions as well as local stakeholders to realise the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) pertaining to water sanitation and hygiene.

With the introduction of the Jal Jeevan Mission in 2019, our nature of work underwent some changes. Since we realised that the government’s programme had many overlapping features with our own, we decided to join hands and collaborate with them. While the government focuses more on creating WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) infrastructure, we focus more on community ownership by building capacity and creating civic consciousness about public resources and assets among local communities.

More than 1,200 water points and partnership with 680 schools and 188 Anganwadi centres across West Bengal

WFP began operations in West Bengal in 1996 with a programme on arsenic mitigation in the districts of North 24-Parganas and Nadia

Could you elaborate on WFP’s ongoing projects in West Bengal?

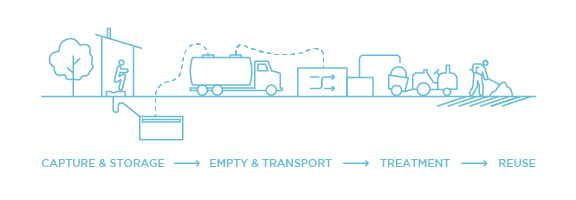

Sujata Tripathy & Dipa Biswas: Our ongoing projects in Bengal are mostly concentrated in South 24-Parganas and Birbhum. However, we also have our presence in Kolkata, Howrah and Hooghly. Overall in West Bengal, we have established more than 1200 water points and partnered with 680 schools, 188 Anganwadi centres and 13 health centres. We have developed 84 community sanitation facilities alongside eight model piped water schemes with household connections. We’ve also been involved in capacity building, behaviour change and monitoring support across the state. We’ve worked closely with the Gram Panchayat at Digambarpur (which won the Government of India’s best Gram Panchayat award in 2018) in the Patharpratima block of South 24-Parganas district. One of our most effective contributions in South 24-Parganas has been helping Gram Panchayats with pit-emptying devices to prevent contamination and other health hazards from open defecation in villages. Presently, WFP is also supporting the Public Health Engineering (PHE) department in South 24-Parganas and Birbhum for accelerating the implementation of the Jal Jeevan Mission.

‘Fluoride content in water is much higher than the safety limit in West Bengal’

The Sunderbans remain one of West Bengal’s biggest climate-related challenges, feels Ghose

What do you see as the biggest challenges or red flags when it comes to water and sanitation in West Bengal right now?

Ghose: One of the biggest issues is the continued presence of arsenic and fluoride in water. Fluoride content in water is much higher than the safety limit in some places of West Bengal. Both arsenic and fluoride in water are silent killers (skeletal fluorosis is debilitating), since both are colourless, odourless and tasteless. They’re affecting the lives and livelihoods of people on a daily basis. This is one challenge that’s entirely preventable if detected early. What we need is effective surveillance, detection, prevention and treatment.

Then, of course, the larger challenge is that of climate change and the need to create effective resilience-building mechanisms against it. This is particularly relevant for the Sunderbans, where flooding and saline water ingress are major issues. Even in Birbhum, which has laterite soil, there’s always a risk of droughts, due to altering climate patterns. We’re witnessing intensification of rainfall, leading to either more run-off water or flooding in some places.

The final challenge is that of developing quality infrastructure in a way that can be managed by the local population. Integrating aspects of water resource management and ensuring that the water used for drinking,cooking and toilet water doesn’t get mixed with fresh water is an important part of this. The huge thrust for infrastructure creation at immense scale brings with it a logistical challenge for ensuring that these are built in the right place and in the right way. Once built, maintaining these infrastructure to ensure continuity of quality services will be a huge challenge.

‘We, as a society, aren’t doing enough… each one of us needs to ask questions’

Ghose argues that the triad of awareness, interest and engagement is what needs to be harnessed to create change in relation to water and sanitation in India

What would you tell our readers about what they can do to help improve water and sanitation conditions at an everyday level?

Ghose: To put things plainly, we, as a society, aren’t doing enough. Everything has to start by talking, but that has to be followed by walking the walk. The Swachh Bharat Mission, for instance, has galvanised a lot of stakeholders and created change, but we can’t wait for the government to do everything. While demanding accountability from the government, the common person must also collaborate with relevant stakeholders whenever they can to conserve water, maintain assets and create awareness.

Each one of us needs to ask simple questions about water because as long as we’re alive, water will touch our lives. So, it’s pertinent that we find out more about water. Who supplies it? Where’s it coming from? What is the quality? One question will lead to another and this way each one of us can find our own way of engaging with water. To highlight the role of everyday people in creating change, let me give you an example of a lake revival campaign in Bengaluru. It took us 12 to 14 years to restore one lake. From what were the lake’s boundaries to who owned it to how we could stop sewage from being poured into it, we had to navigate a bunch of issues before being successful with our objectives. It took time and patience to generate awareness, interest and engagement. Without that, it’s not possible to move people from the side of the problem to the side of the solution.

How did the collaboration between Flying Squirrel Holidays and WFP come about, and what is the present scope of social tourism?

Niloy Nag: This is the second time that we’re working with WFP. The first was in 2017, and we suppose they went back with some good memories of their tour of West Bengal! So, in 2022, when they sounded us out about their plans, we were happy to be their partner of choice.

Social tourism is an emerging area for travel and education. People across the world are now looking to venture out for reasons beyond leisure and business. They’re looking at more meaningful ways of connecting with local communities, contributing to the development of societies and making an impact in areas such as education, drinking water, housing, sanitation, among others. The government is doing all it can in extending support across all these areas. Social tourism opens up avenues for volunteerism where more people can be involved in strengthening the social fabric that will further boost the economy, inspiring innovative ideas for capacity building and opportunities to attract tourists to the country. We, at Flying Squirrel Holidays, are willing to go that extra mile in the development of our state through social tourism.